The first step to a good crosswind landing is to select a runway with the least crosswind factor. Ask for a change of runway if required.

The second step to any good landing is a stable approach. The stable approach begins with a correct circuit pattern. On each leg of the circuit, you need to keep crosswind correction in mind and continually make appropriate control and power inputs.

In order to avoid being blown closer or further from runway due to crosswinds on downwind, point aircraft nose sufficiently into the wind and pick up a ground feature so as to maintain the track. If you do not cater for it on downwind, aircraft will be too close or far from the runway. If this happens base leg will not work out.

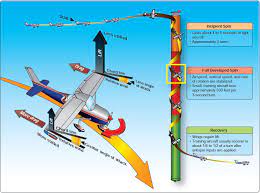

The base leg and base-to-final turn are undoubtedly the most critical parts of a crosswind approach, because it is here that either excessive height is lost or the final turn is delayed leading to ‘S’ turn. So in order to achieve a stabilized approach, make corrections on the base leg. With a headwind on base, delay reducing power early and if required add power to avoid getting low. Conversely, with a tailwind, the base leg will be quicker than you’re used to. In such a case reduce power early and commence turn early. If the final turn is delayed, do not make the mistake of increasing the bank angle to prevent overshooting the final leg. This may result in an inadvertent stall and spin — one accident type you’re not likely to walk away from.

On the final leg, the aim is to touch down with the nose straight down the runway without any drift. This is when technique and experience really count. To achieve this airplane should track straight down the centreline of the runway. There are two techniques that are generally used during crosswind.

Crab technique. The objective of this technique is to maintain the wings level and point the nose sufficiently into the wind to start crabbing along the extended runway centerline. On approach as you descend, the wind direction and strength will continue to change. Look at the far end and near the end of the runway and keep correcting for offset to keep the aircraft track straight towards the runway centreline. The trick is to look at the far end of the runway and you will find you are automatically correcting the offset.

Some pilots continue the crab until just before the touchdown point when they quickly align the airplane nose with the runway centreline by applying the rudder and lower the wing towards the upwind side to counteract the drift due to crosswind. Do not do it mechanically. Once again the trick is to shift your gaze to the middle/far end of the runway and then try to keep yourself on the centreline or parallel to it.

Side slip or cross control technique. The sideslip technique is to maintain the aircraft heading aligned with the runway centreline. The aircraft is maintained along the centreline by using aileron into the wind and opposite rudder. This places the aircraft at a constant side slip angle. A constant aileron must be applied to maintain the sideslip value. In this technique, the airplane will be cross-controlled, making aircraft stall speed higher. As a word of caution, set your approach speed a couple of knots above your usual approach speed to make sure you have some margins to play with.

Which one you prefer will likely depend on how you were first taught though the crab technique is the most commonly used technique for crosswind landing.

TIPS

- In strong crosswind conditions, it is sometimes necessary to combine the crab technique with the side slip technique.

- Also, remember that the reported winds are measured at only one localized point. The winds speed and direction are continuously changing on the approach.

- Use a crosswind component chart to calculate the crosswind component. You should keep a crosswind component chart in the airplane or your flight bag, but if the chart isn’t handy, here are some rough gauges. If the wind is 30 degrees off the nose, the crosswind component is half the total wind speed. If the wind is 50 degrees off, the crosswind component is roughly 75 percent of the wind speed. For 70 degrees, the crosswind component is about 90 percent of the wind speed.

- If the crosswinds are beyond the airplane’s demonstrated crosswind limitation which are published in the pilot operating handbook then consider diverting where winds are within limits. Otherwise you risk to side-load the landing gear, damaging the airplane or having an accident.

- With strong winds, it is quite likely that you’ll touch down on one wheel — the upwind wheel — if you’re using the sideslip technique. But landing on one wheel shouldn’t alarm you. As long as your power is idle and your speed slow, the second wheel will soon follow. And the need to apply wind correction doesn’t stop just because the wheels have touched the ground. This is a common mistake. So once you’re on the ground, get your ailerons into the wind and apply rudders to maintain a straight track down the runway until you’ve slowed the airplane sufficiently to safely taxi to your parking spot.

Happy landing. Be safe.