The unfailing and correct use of normal checklists is an important SOP and an essential part of good flight crew discipline.

When I began my ab initio flight training in military, the ultimate aim was to – pass solo check which used to be after 14 training flights. Going Solo means single pilot operation, where you have no one else to assist and help with check lists or flight path management or avoiding distractions. We memorised checks and procedures and then execute them while managing the flight path without Flight Director or Autopilot. It was a herculean task to be achieved in just 14 flights. The method employed to achieve this was simple and time tested. We had to score 100% in ‘Gen Test’ which used to comprise of checks, procedures and emergency items.

The major emphasis of training was to be able to operate as single pilot. In single pilot operations, pilots have only themselves in the cockpit to catch mistakes. We learnt to use letter sequence called as mnemonics to run through checks and procedures. In military operations it was emphasised to run through checklist with the help of memory and refer to QRH only in case of doubt. Referring to QRH was almost impossible as we did not have luxury of autopilot back then.

Fast forward to days of Air Force Test Pilots School. We were expected to fly more than 8 types in short span of 10 months. It was next to impossible to remember the check list of all these different aircraft ranging from supersonic fighter to transport aircraft to training aircraft. We were not only expected to fly but also conduct test points on these totally unfamiliar aircraft. I learnt to use the checklist in a step by step manner as a do list. It was time taking (not efficient) and very very frustrating because it required moving focus and eyes from checklist to switches and dials in the cockpit and then back to checklist for each of possible dozen steps.

Jump to 21st century, as technology improved, the military fighters were better equipped. I learned to operate using the flow/checklist. This was much safer and efficient method in which the pilot conduct a specific sequence of memorized actions without reference to a checklist. Then, once this “flow pattern” is completed, the pilot reads the corresponding checklist aloud, visually confirming the actions were taken as the checklist is read.

In commercial aviation, a checklist could be done by two ways: challenge-response and do-verify. In both the methods, the first step is the flow. Challenge-response involves response from the Pilot flying, thus it is introduces additional safety. While, Do-verify involves completing the flows and the checklist is both challenged and responded by Pilot monitoring alone. This is employed for less critical checklist only.

Omission of a required action or performance of an inappropriate action are primary causal factors in approach and landing accidents, and are cited (Flight Safety Foundation, 1998-1999) as causal factors in:

- 45 percent of fatal approach and landing accidents

- 70 percent of all approach and landing accidents

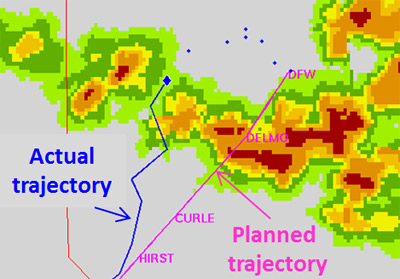

The same aircraft could have different checklist and flows in different companies. You could also develop your own flows depending on type of operations you are undertaking like Low Visibility or adverse weather or in icing conditions. Every time, you undertake operations in special condition, it is worth reviewing aircraft MEL, pilot proficiency and call outs, airfield operational limitations if any, aircraft performance and limitations. This is my special flow when undertaking operations when weather is not what I like it to be.

Whenever, I was flying a new aircraft as a Test Pilot, I always first did checklist sitting in the aircraft and chair flying the procedure. This helped me develop a pattern and subsequently a flow what I called as ‘Designing Flow’. I would also take time off to go through emergency items and non normal checklist while sitting in the aircraft. If an opportunity presented, I would discuss the procedures and flows with more experienced pilot and further refine my flows. This made my “designing flow’ technique more proficient.

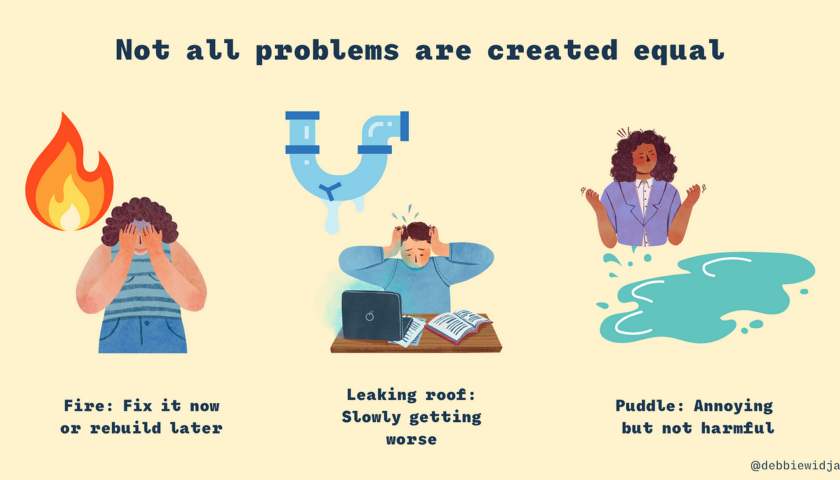

While flying different type it was not possible to remember checklist however, it was always easy to recollect and remember a pattern (muscle memory). But then what about emergency items like reject, fire/smoke or flame out. This situation could lead to overload easily when combined with stress. But then if you look very closely, the actions are always the same – to prevent the situation from getting worse. All your actions are based on that. As I gained experience as a Test Pilot, I further refined my flows. I started doing Pre- pre-flight which included switch locations of emergency systems (kind of blind fold checks) and checking aircraft limitations. This would further prepare me for any contingency and help me get in the groove when flying more than 2 types in a day. Yes to be honest, the job was stressful because it was beyond normal but it was fun as well as extremely satisfying.

While converting to a new type, I always look for flows. Some of these flows were self-taught, others were company requirements and many I picked up as recommendations from fellow pilots. Usually they were the result of missing something or optimizing a procedure after experience in an airplane. In addition, I always do some self debrief when a mistake comes up. Flying with another more experienced pilot is always helpful but more than often I have learnt a new technique or perspective form pilot fresh in the role.

Every flight is different and each flight presents a learning opportunity. If you find yourself forgetting or not verifying something, consider adding that to your flow to prevent the mistake from happening again. Someday, we all will be a proverbial perfect pilot. Till then…

Be safe and Plan well.